In Moldova’s Gagauzia, Pro-Russian Fugitive Seeks to Sway Pensioner Vote

In Moldova, pro-Russian propaganda is seducing pensioners ahead of an October election and a referendum on EU membership. In autonomous Gagauzia, where ties with Moscow are strong, older residents are being courted with cash from a fugitive oligarch.

Seated on a blue bench in front of his house, 72-year-old Piotr [not his real name] spends hot summer afternoons reminiscing about the past in Avdarma, a village in the autonomous region of Gagauzia. Lining the quiet street, traditional water wells, ancient tractors and colourful gates stand as emblems of the Moldovan countryside. Here, time seems to stand still.

Nostalgia-struck Piotr would much prefer to travel backwards – to a past when the village was lively and neighbours helped each other out.

“There used to be many people here, including children,” said the pensioner, a grey cap covering his sun-tanned forehead. Now, many houses stand empty.

As is often the case in Moldova, many Avdarma families have moved abroad, leaving their ageing parents behind. Piotr’s wife left 30 years ago, followed by his daughter.

“Many women leave to make money,” said Piotr, who like other Gagauzia pensioners quoted in this story spoke on condition that his real name not be used. “Because of this, some men have even died of grief.”

The retired farmer now lives with his son on a monthly pension of 200 euros. It’s enough to survive, he says, because he uses firewood to cook and heat the house instead of natural gas, which has soared in price in recent years.

Despite recent increases of roughly 10 per cent, the average pension in Moldova still languishes at around 150 euros per month. To make ends meet, many elderly people from Gagauzia rely on the help of their children, most of whom live in Russia or Turkey.

Recently, however, pensioners in Gagauzia have been receiving other forms of ‘help’, just as Moldova’s pro-European president, Maia Sandu, begins her bid for a new term in elections in October and the country votes on whether to write its European Union accession ambition into the constitution.

A few months ago, people introducing themselves as “representatives” of fugitive pro-Russian oligarch Ilan Shor knocked on the door of a house in Avdarma belonging to 85-year-old Elena [also not her real name].

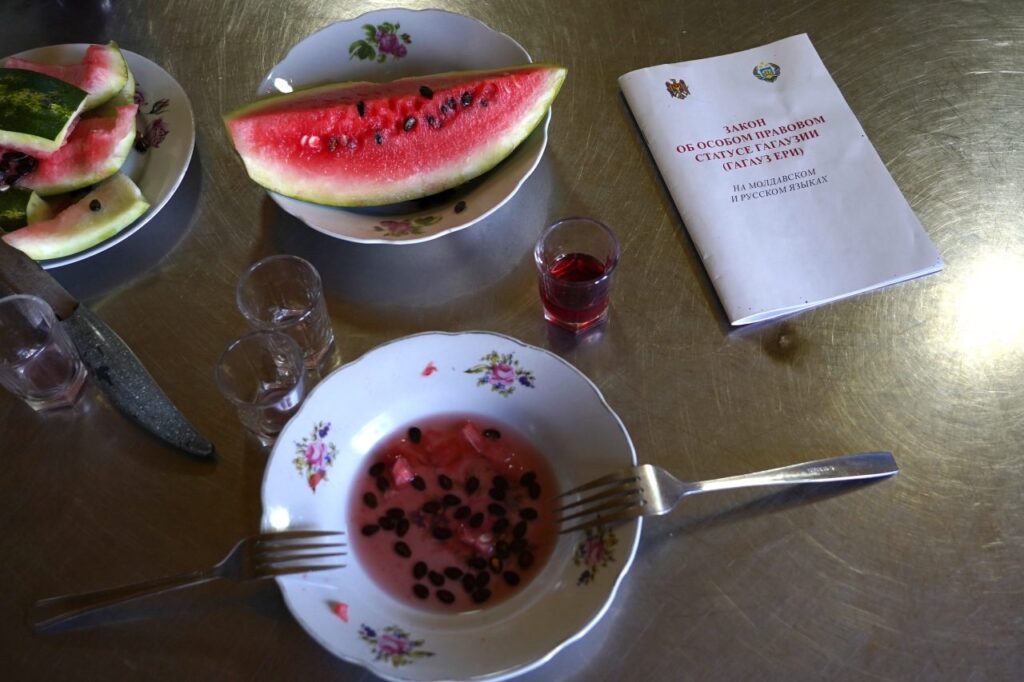

“They wrote down my information and asked for my pension documents,” said the mother of 12, speaking in Gagauzian, a Turkic language. Shor’s people offered Elena a monthly stipend of 100 euros via a Russian payment card called ‘MIR’ under a deal signed in April by Russian bank Promsvyazibank and Evghenia Gutul, the current leader, or Bashkan, of Gagauzia. Gutul is being tried for the illegal financing of the Shor party, which was banned last year, but she remains popular in Gagauzia.

The origin of the monthly payments remains unclear. The Bashkan stated that it would be made available by “partners from Russia”. But local media reports say the real sponsor is a non-profit called Eurasia and linked to Nelli Parutenco, the Shor party’s former treasurer.

Israeli-born Shor was sentenced in absentia last year to 15 years in prison for masterminding the theft of almost $1 billion from the Moldovan banking system, but his conviction and his close ties to Moscow seem not to have hurt his popularity in Gagauzia, where many residents like Piotr and Elena hanker for the Soviet past and are vulnerable to pro-Russian propaganda, regardless of Russia’s war in neighbouring Ukraine.

“Pensioners are associating Russia not with the war or with an aggressor state, but rather see it as a state which was responsible for their good life when they were young,” said Tatiana Cojocari, a sociologist and expert on Russian foreign policy.

“They think that Russia is the same as before, and if money is coming from Russia, it doesn’t matter that the politician is corrupt or convicted, it means he’s trying to help them.”

‘We are living in poverty’

Brought from Turkey by the Russian Tsar in the early 19th century, Gagauzians are one of many ethnic minorities in Moldova. They also form one of the most pro-Russian populations in the country, with pensioners particularly nostalgic for when Moldova was part of the Soviet Union.

Gagauzia received its autonomous status in 1994, a few years after Moldova became independent. Russian is still widely spoken in the region and its residents’ cultural and linguistic ties with Russia mean many are hostile towards Moldova’s current pro-European government. Few speak Romanian, Moldova’s official language.

Recalling the Soviet period, Piotr said: “We were living in peace, and if you were sick, you could go to the same hospital as a high-ranking person, it was free of charge.”

Like many other Gagauzians, Elena is a Shor supporter and believes Sandu has little time for Gagauzia.

“Maia doesn’t love the Gagauz people,” she said.

Whether or not Sandu really does “love” the population of Gagauzia, analysts say that low internet literacy and a lack of independent Russian-language media further reinforces the vulnerability of pensioners to fake news, propaganda and populist gestures.

“Propaganda and disinformation work by using something you believe in, and playing on it,” said Cojocari. “And when local politicians reinforce these ideas, it’s even more powerful.”

Moldova’s National Bank says MIR transfers are not technically possible, much to the consternation of Gagauzia’s pensioners.

“We are living in poverty,” said Dmitri [not his real name], a retired engineer who had hoped to receive the 100-euro top-up. He and his wife sat in the shade of a tree on a scorching July afternoon.

The couple spend much of their combined income on medicine for Dmitri’s wife, leaving little for other expenses.

With many young people living abroad, pensioners in Moldova represent roughly 25 per cent of in-country voters, according to figures from the National Bureau of Statistics.

“Older people are one of the most vulnerable categories in Moldova”, said Cojocari. “If you manage to mobilise older people to vote for you, you’ll have enough votes to enter parliament.”

Local politicians know how to turn this reality to their advantage. For many pensioners, the monthly allowance promised by Shor through the MIR systems would double their income – an impact that can only shape their political views in his favour.

“When you don’t have a good economic situation, when you’re not satisfied with the local services, and you don’t have the life you used to have when you were young, you’ll be unsatisfied with the political situation in the country. You’ll try to find ways to improve your life,” said Cojocari.

Paid protesters

MIR is a Russian state-backed card payment system created to protect the Russian economy against sanctions imposed over Moscow’s annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula in 2014. Amid restrictions on the use of Visa and Mastercard, MIR has grown in popularity but it is illegal in Moldova, where the National Bank has declared its use “physically impossible”.

In Moldova, the only place where MIR payments are possible is Transnistria, a region controlled by pro-Russian separatists since a short war in the early 1990s following Moldovan independence.

Moldova’s prosecutor general, Ion Munteanu, said the promotion of MIR bank cards for Gagauzians was one of several attempts to “illegally finance various actions that would compromise the sovereignty of the state”.

Shor is widely seen as one of Moscow’s main vectors of propaganda in Moldova. Last May, from Moscow, he launched a pro-Russian Moldovan opposition coalition called Victory.

Within Moldova, Shor’s associates regularly organise anti-government protests as well as gatherings in support of Gutul whenever she appears in court. Pensioners are invariably a big part of the usually small crowds. One said he had been paid to turn up.

“People go to protect their rights, and at the same time they are offered money, so why not take it?” said 69-year-old Stepan, before clarifying that he would attend “even without compensation”.

Vadim, another pensioner and former local secretary of the Soviet-era Communist Party, said:

“Usually, pensioners attend these kinds of protests because they have more free time as they don’t work, as well as for the financial compensation. And because of nostalgia for the past.”

Widowed eight years ago, the former engineer spends his time tending to his animals, vegetables and vines. Most of the food he eats is home-grown. In his front yard, a silver Soviet Lada stands as a relic from the past. “Today’s youth, they don’t know the life we lived.”

Ivan Cîlcic, a member of the Gagauzian veteran community and a critic of both the Moldovan government and the current Bashkan of Gagauzia, said pensioners are offered between 400 and 600 Moldovan lei [20 to 30 euros] per protest.

“People are brought to the protests by buses. Sometimes they don’t even know where they are going,” he said, sipping a glass of home-made cherry liqueur.

“Those protestors are generally not interested in politics, they prefer not to think. On the one hand, I’m angry at these people, but I also understand the pensioners.”

Some distrust Shor

The government in Chisinau accuses Shor of stirring up separatist sentiment among the Gagauzians. Some support independence but do not trust Shor.

“We always wanted autonomy to protect our culture and language, but the opposite happened,” said Ivan, a tall man with an immaculately-trimmed grey beard and aspirations to create his own pro-independence party in Gagauzia. “The government didn’t develop our language and didn’t want us to develop as a nation.”

Shor, however, is not the answer, Ivan said. “He’s using Gagauzia as a bridge to come back to Moldovan politics. Ilan Shor is sucking Gagauzia into his politics and is putting us on an equal level with him – and that’s what the world sees.”

But while opinions on Shor may vary, dissatisfaction with Sandu and the government appears universal in Gagauzia. Some Gagauzians say they will boycott the election and the EU membership referendum. Others vow to vote ‘No’ in the plebiscite but say they have yet to choose whom to back among the presidential candidates, most of whom lean towards Russia.

Piotr expressed concern at the plethora of presidential pretenders.

“There are more than ten candidates for the presidential election,” he said. “Can you imagine if they all come here and try to win votes? Some with money, some with promises… it’s going to tear Gagauzia apart. And then it will take us 10 years to reunite.”

Such a catastrophic scenario seems unlikely, but the populist promises will only grow, influencing political choices and the future of a country full of contradictory hopes.

Written by Maria Gerth-Niculescu

Leave a Reply