Refugees in Transnistria Come to Moldova for Help

Since the war began, around 10,000 Ukrainians have fled to Transnistria, a region controlled by pro-Russian separatists. We learned why, as hundreds crossed over to Moldova for aid packages.

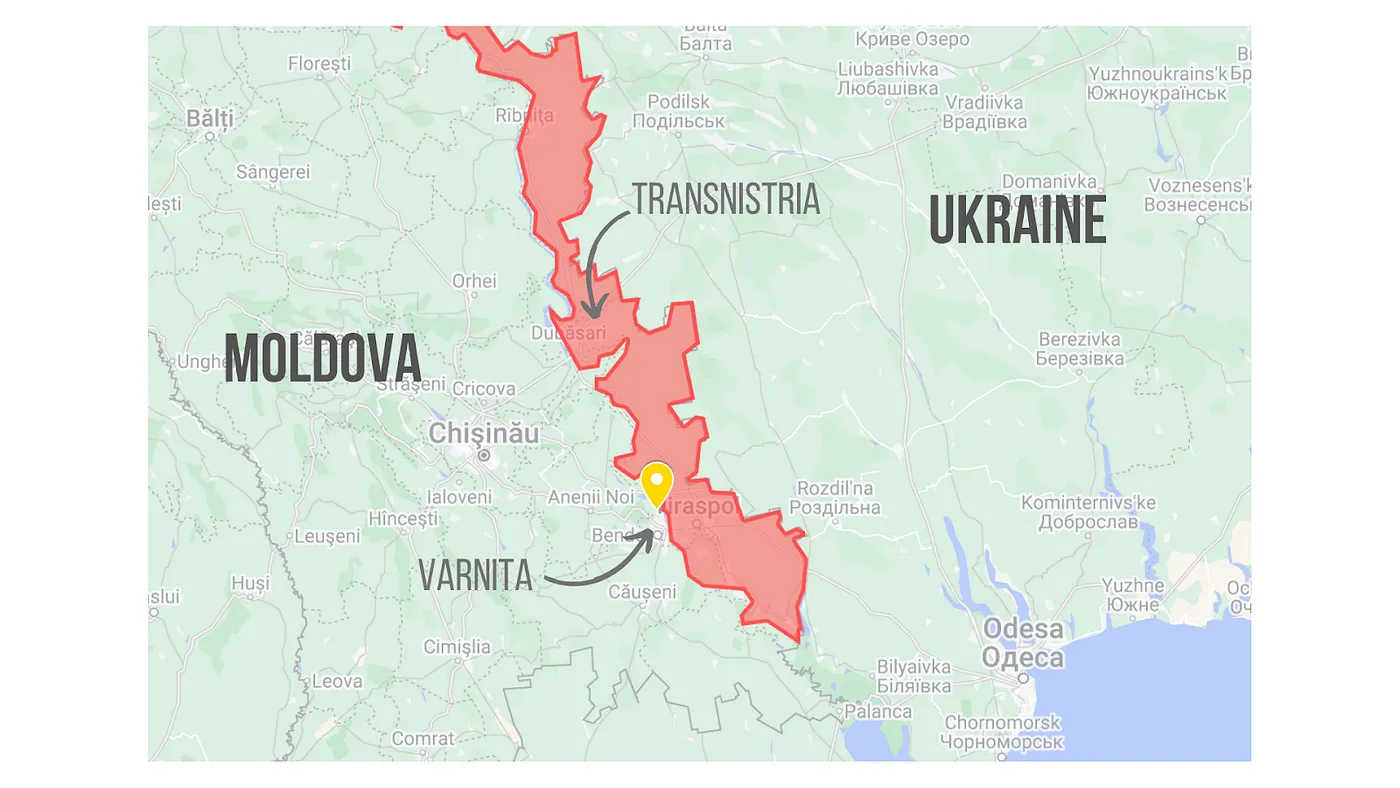

On a warm September day, we drove through the so-called Transnistrian checkpoint in Moldova, arriving at the Moldovan village of Varnita. Transnistria is just across the Dniester River from here. Internationally recognized as part of Moldova, Transnistria was overtaken by the pro-Russians in the 90s civil war.

Its so-called capital, Tiraspol, is about a 30-minute drive from here, and Moldova’s official capital, Chisinau, is roughly an hour away. The Ukrainian border is also nearby. It soon becomes apparent that the small village of Varnita serves as a gateway to three distinct worlds, each with its language.

Volunteers from the Moldovan NGO Katalyst Kitchen and Norwegian Refugee Council assemble food and hygiene packages for Ukrainian asylum seekers living in the breakaway region. Many of the charity workers are Ukrainians themselves. Today, at least 300 people are expected to collect help. These are the lucky ones, not everyone made it to the limited list.

A diverse crowd forms a long queue — babies, children, the elderly, and the young. An old Moldovan gas station swiftly transforms into a logistics center.

Those in need present their Ukrainian passports to receive packages tailored for babies, kids, men, and women. Broad smiles appear on children’s faces when they reach for their white paper bags. There are little juice boxes, fruit, and puffed snacks for them. The kids also get mini tennis rackets and balls.

The bags are filled with detergents, sponges, and soaps. Most of them have basic food. The people thank the donators and quickly drag their heavy bags to the car and drive off or walk to the bus station. Only a few stay to chat. Everything is done quietly, with a lot of unspoken words lingering in the air.

Viola Mozhaieva, a Ukrainian refugee from Transnistria, is a coordinator here. She told us that finding aid as a refugee in Transnistria has become increasingly rare.

NGOs and civic activists operate in a repressive environment there, concluded the Freedom House, a democracy watchdog group, last year. The Transnistrian authorities harass and monitor groups that work on human rights issues. They also control the public media. There is a lack of fundamental rights like the freedom of expression. The link to Russia is still strong. About 1,500 Russian soldiers still live in Transnistria. The territory solely relies on Russian gas that is then partly converted into electricity in the local plant. In this context, economic opportunity remains very limited.

“It’s very tough for people in Transnistria,” Viola explained. “Unfortunately, there’s virtually no assistance, mainly due to lack of funding. We’re fortunate if we receive food aid once a month or every other month. But people need to eat daily!”

Some asylum seekers are already feeling desperate. “They’re becoming aggressive, realizing there’s no more hope. The war continues, and the conditions worsen,” said Viola, who sees it as her mission to make sure those in need know about the possible help.

Considering all this — why stay in a Russia-friendly place with so little support and even freedom?

“We simply didn’t know where else to go,” 82-year-old Tamara, a native of Crimea, told us. She traveled to Transnistria with her daughter, granddaughter, great-granddaughter, two cats, and a dog. When they arrived, they didn’t know anyone. “We just gathered our family and came here, unsure of our destination,” Tamara explained. “But kind-hearted people took us in.”

An Odesa family with three children wanted to settle in Chisinau, but the father feared he wouldn’t find work there and chose a Russian-speaking Transnistria instead. Their baby girl was born there after the war had started. The salaries are lower there, but so is the rent and everything else, they explain. Now, they are just waiting for the fighting to be over to return to Ukraine. “The birth of our child gives us hope,” adds the mother, who asked her name not to be published.

Ukraine, bordering the breakaway region, has been a significant trading partner for Transnistria, and Ukrainians make up about one-fifth of its population. Naturally, many came here to stay with family and friends. But some simply couldn’t go further, Viola explained. There are many people with disabilities.

Nearly a million border crossings

The UN’s report concludes that low living costs, family ties, and previous residence are some of the main reasons for choosing Transnistria as a refuge. The problem is that they don’t usually register themselves. As of this summer, only 76 refugees — out of some 10,000 — in the Transnistrian region had officially filed for protection.

According to the UN, obtaining the necessary documents about the residency could have been difficult. The refugees also needed a Moldovan mobile number for registration, which could be another obstacle. Even the absence of a Moldovan entry stamp in their passports could make the registration harder.

The requirements were eased in September this year, said Monica Vazquez, the UN Refugee Agency’s external relations officer in Moldova. Now, refugees only need to submit a self-declaration form, accessible online.

The UNHCR operates through local partnerships across all of Moldova, including the Transnistrian region. They see that people get tired of helping. Many refugees have been in Moldova for at least a year. “It’s natural for them to start working and become self-reliant,” said Vazquez. “But the humanitarian need persists, and it’s crucial to keep supporting at all levels.”

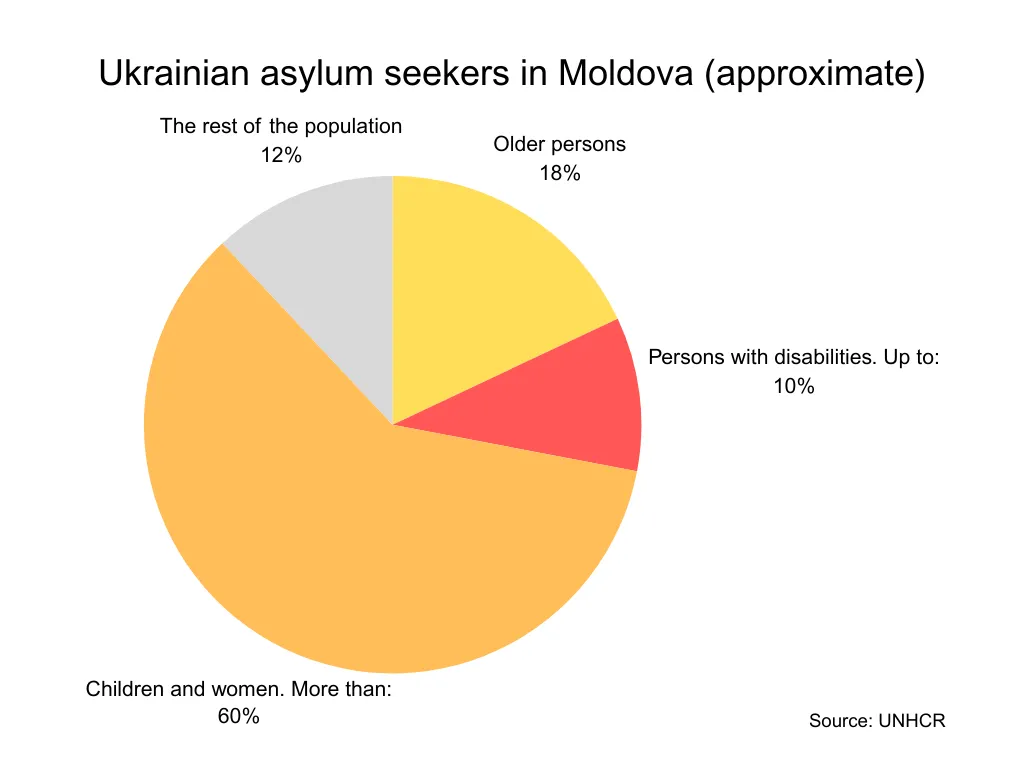

Moldova hosts some of the region’s most vulnerable refugee populations. “18 percent are older persons, 7–10 percent are persons with disabilities, and over 60 percent are children and women,” Vazquez specified.

Moldova has been instrumental in assisting Ukrainian refugees. As of November, over 113,000 Ukrainian refugees have settled in Moldova, with nearly a million crossing the Moldovan border since the war started in February 2022. Additionally, almost 700,000 Ukrainians have returned to their war-torn homeland through Moldova since then.

“What Moldova has achieved is extraordinary on every level,” concluded Vazquez. “It’s remarkable how they’ve stepped up, opened their doors, and rushed to assist! Moldova’s response has been incredibly forward-thinking!”

Leave a Reply